November 10, 2015

Ikebana: The Art of Flower Arranging

What is Ikebana?

Ikebana is the ancient Japanese art of flower arranging. The name comes from the Japanese ike, meaning ‘alive’ or ‘arrange’ and bana meaning ‘flower.’ The practice of using flowers as offerings in temples originated in the seventh century when Buddhism was first introduced to Japan from China and Korea, but the formalized version of Ikebana didn’t begin until the Muromachi period around the 15th or 16th century. These arrangements have since become more secular, displayed as art forms in people’s homes. However, Ikebana is seen as more than just decorative, it is a spiritual process that helps one develop a closeness with nature and merge the indoors and outdoors.

Principles of Ikebana

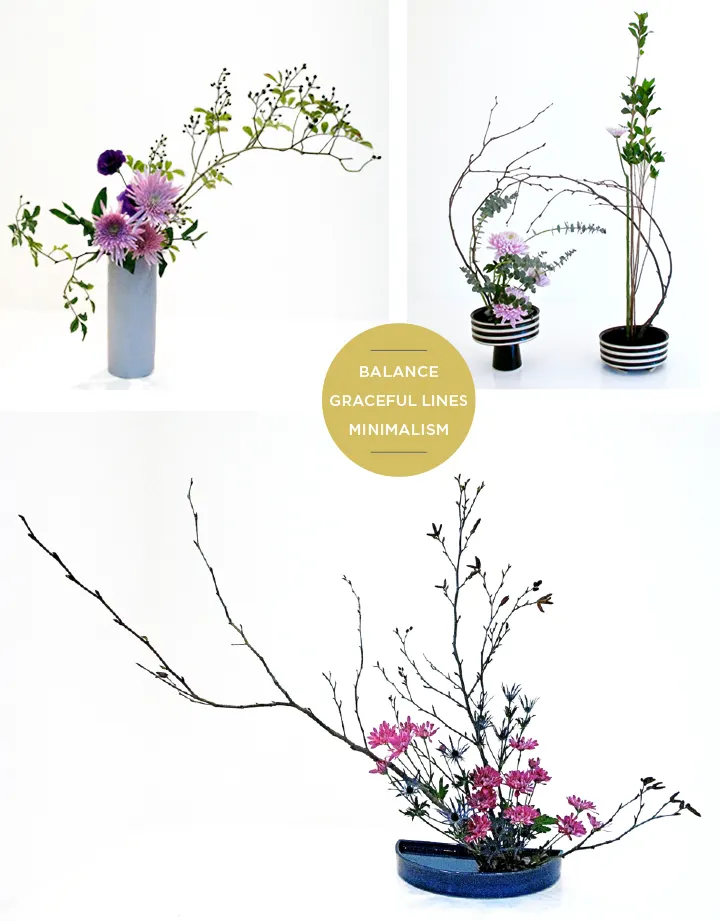

Ikebana has become an artform that is associated with a meditative quality. Creating an arrangement is supposed to be done in silence to allow the designer to observe and meditate on the beauty of nature and gain inner peace. Seasoned designers realize not only the importance of silence, but also the importance of space, which is not meant to be filled, but created and preserved through the arrangements. This ties into other principles of Ikebana including minimalism, shape and line, form, humanity, aesthetics, and balance.

Schools of Ikebana

There are over 3000 schools of Ikebana. The oldest known school is Ikenobo. Ikenobo began at the Rokkaku-do temple in Kyoto where the Ikenobo family had long been head priests. The first style created by this family was Rikka, which was an evolution of early Buddhist floral decoration where flowers were used to embody the concept of the cosmos rather than for their superficial beauty. Over the next few hundred years, Ikebana continued to grow and develop, becoming not just a staple of Buddhism, but a staple of Japanese culture as a whole. This became even more apparent in the late nineteenth century when Western culture was introduced to Japan. Some flower masters embraced Western blooms and incorporated them into the arrangements. The most notable was Unshin Ohara who broke away from the Ikenobo School and started the Ohara School. He soon created the Moribana style, meaning ‘piling up of flowers,’ which took a much freer approach than previous styles, but still emphasized uneven numbers and asymmetry in the arrangements. This style soon became one of the most popular. There are three common Moribana styles—upright, slanting, and water-reflecting—with many variations within each style. Beginner’s usually start by learning the upright style.

What You Need to Create a Moribana-Style Arrangement

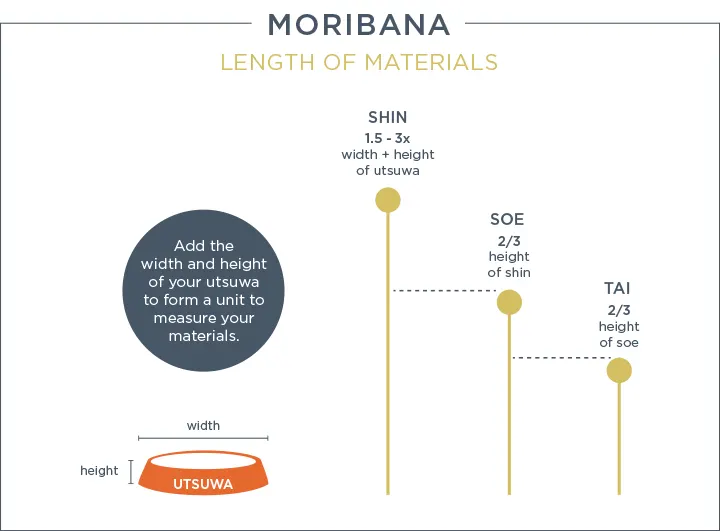

One of the most distinctive features of Moribana is its use of shallow containers, or utsuwa. Kenzan, which are similar to floral frogs, must be used in conjunction with these containers to allow flowers and branches to be placed in upright and angled positions. There are three main types of flowers and branches used. The longest branch, called shin, represents heaven. The medium branch, soe, represents man. And the shortest branch, tai, represents earth. Additional flowers to accompany these can be used as well.

Length of Materials

The branches and flowers—shin, soe, and tai—are all measured in relation to the utsuwa. To determine the proper lengths of these elements, measure the height and width of your vase and add these measurements together. Shin should be no more than three times this sum. Soe is two-thirds of shin, and tai is two-thirds of soe. If shin and soe are branches, accompanying decorative flowers, called jushi, will be half as long as shin, soe, and tai. Remember to take into account the depth of the vase and angle placement when deciding how long to cut your branches and flowers.

Arranging Materials

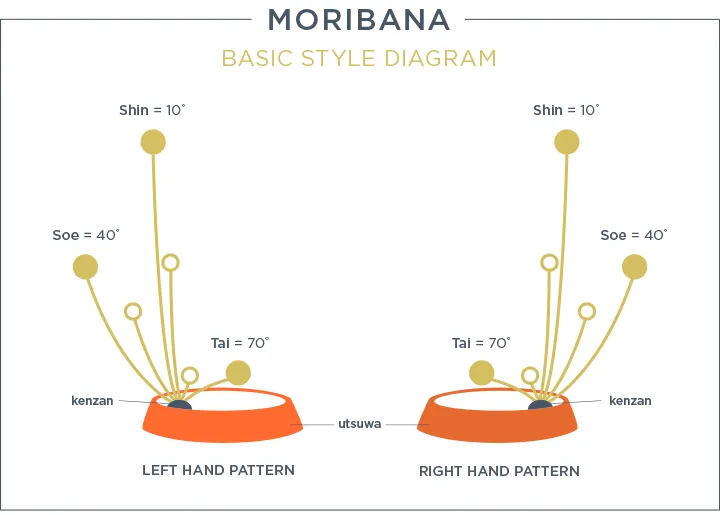

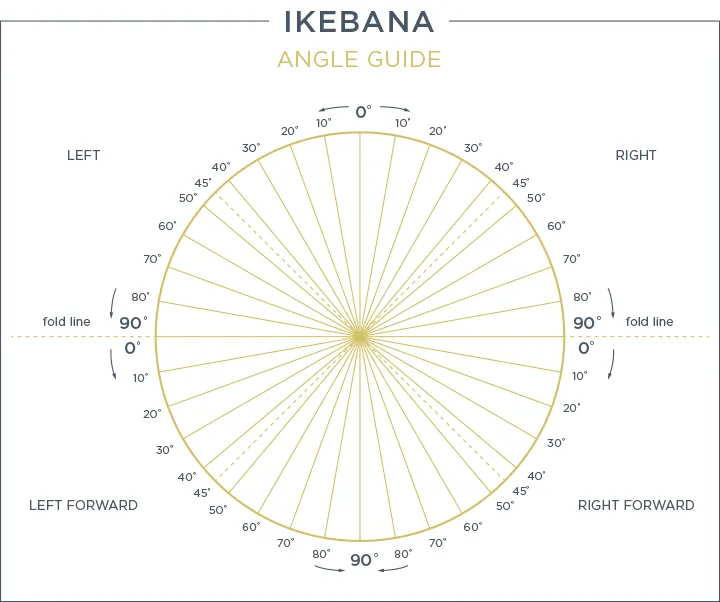

Moribana arrangements are like sculptures. They take advantage of three dimensional space in every direction. You can create the most basic style by placing shin at the center back of the kenzan, 10 degrees to the left and 10 degrees forward. Place soe 40 degrees to the left and 40 degrees forward. Place tai 70 degrees to the right and 70 degrees to the front. Determining angles in two directions may be challenging at first. To make it easier, you can print and fold the Ikebana Angle Guide below to help you understand how to position your flowers and branches.

Flowers to Use

The flowers and branches used in Moribana arrangements are chosen not only for their beauty, but also for how they interact with one another and with the style of Moribana as a whole. Upright arrangements often use stiff, straight branches for shin, while the slanting style is softer and projects a sense of movement by utilizing grasses and branches that grow slanting down. When choosing flowers and branches for your arrangement, it is important to keep in mind that there are endless possibilities to choose from. The most important thing isn’t a specific flower, it’s how all the pieces work together to create one expressive, meaningful piece that plays with the idea of space.

Image Credits

Principles of Ikebana, all photos and Schools of Ikebana, photo 3: Courtesy of The Ikebana Shop on Flickr

Schools of Ikebana, photos 1, 2, and 4: Courtesy of Katerina Mezhekova on Flickr and keiseiflowers.wordpress.com/

Ikebana Flowers:

Thistle: CC Image courtesy of Jimmie R Johnson on Wikimedia Commons

Dahlia: CC Image courtesy of Loïc Evanno on Wikimedia Commons

Peony: CC Image courtesy of MarcusObal on Wikimedia Commons

Misty Blue: CC Image courtesy of Derek Ramsey on Wikimedia Commons

Baby’s Breath: CC Image courtesy of Casey Fleser on Flickr

Great Burnet: CC Image courtesy of Hectonichus on Wikimedia Commons

Sources

http://www.stephencoler.com/whatisikebana_en.htm

https://www.slideshare.net/followtheraven/ikebana-25063265

https://makezine.com/projects/ikebana-101/

http://www.stephencoler.com/ikebana_history_en.htm

https://www.presentationzen.com/presentationzen/2009/09/0-design-lessons-from-ikebana.html

http://www.stephencoler.com/material_en.htm

Ikebana: The Art of Arranging Flowers by Shozo Sato

Ikebana with the Seasons by Kozan Okada